How do we calculate the number of litres?

We’re often asked: “How do you actually calculate how many litres of clean drinking water you produce in your water projects?”

That is a good question and we are happy to answer it. Because at Made Blue Foundation everything revolves around transparency: we want to deliver on every litre we promise.

Data from water projects

To calculate how much clean drinking water a Made Blue water project produces, we look at three things:

- What type of facility is being constructed?

- How many people will use that on a daily basis?

- How long can the facility function reliably?

We base our calculations on official figures, technical measurements, and realistic lifespans—not on theoretical maximum capacity. We also deduct 20% from the calculated litres to avoid counting litres that are wasted in practice.

Amount of water per type of water supply

To ensure fair and comparable calculations, we also work with fixed assumptions for different types of facilities:

- Hand pumps: 20 litres per person per day.

- Schools: 5 litres per pupil per day.

- House connections: 60 litres per person per day.

These values have been deliberately chosen to be conservative – better to be a little too cautious than too optimistic. This way we can be sure that every reported liter is actually delivered.

How many people use the water?

Our implementing partners have decades of expertise and work closely with local governments and regional water authorities. They know exactly how many people live in a village or neighborhood, how many students attend a school, and how many of them depend on a single water point.

They also know how much a pump, source, or pipeline can realistically deliver at the location where it becomes available. They then consider capacity, water supply, seasons, and usage patterns.

The lifespan of a water supply

For our calculations, we use an average project impact of 15 years. This aligns with international guidelines for rural water supply systems, as used by organizations such as UNICEF, IRC WASH, and the World Bank, provided maintenance and management are guaranteed.

Components like pumps and batteries have a shorter lifespan and typically need replacing after 5 to 10 years. We incorporate this into our project plans and pay for it through local management models and water tariffs.

Heavier infrastructure—such as pipelines, concrete platforms, or reservoirs—can often last 20 to 30 years or longer with proper use and maintenance. In short: 15 years isn’t a guarantee, but a conservative estimate.

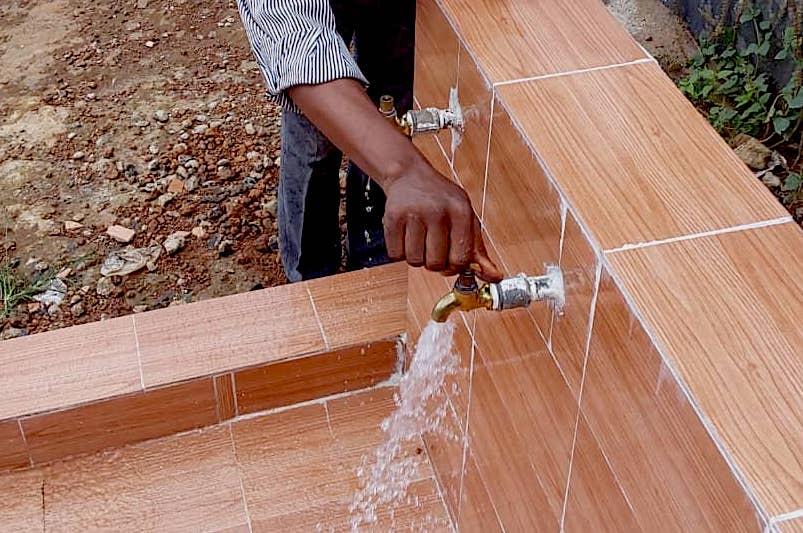

From tap to litres in practice

We also check our calculations in practice because the theoretical capacity is certainly not always achieved in practice.

Imagine a public water supply with a borehole, a pump and ten taps. In principle, a tap can fill a 20-litre jerry can 240 times a day – that’s 4,800 litres per tap per day.

But in reality, the pump sets the limit: it can deliver about 1,000 litres per hour.

Since people usually only collect water during the day – about 12 hours a day – the total capacity amounts to 12,000 litres per day. That is much lower than the theoretical 48,000 litres.

Count, compare and adjust

We continuously monitor which water supplies our projects have actually delivered upon completion. We use this to calculate the litres for the next 15 years, after which we deduct another 20% because something can always go wrong.

We add up all those litres to one big, global water balance. We always compare these with the number of liters we have promised to achieve to our donors. This way we can be sure that the figures are correct – and that every litre we communicate actually flows from a tap somewhere in the world.

Transparency as a starting point

For each project, we clarify which assumptions we use, which losses have been included, and what our figures are based on. This way, donors can trust that every litre in our reports is not just a calculation, but a real litre of clean drinking water, delivered to people who really need it.

An independent board oversees this, because transparency is central to Made Blue – from source to tap, and from litre to life.

Make litres of water available too

Convert the water you save, use, serve or sell with your company into the same number of litres of clean drinking water in developing countries.

This way, you make a tangible impact and increase your company’s meter reading. There’s more ways to support us than you might think.